On this week’s edition of Borrowed Taste, we have my friend Bella to grace us with her insight on Love Island. Bella and I have been friends since the first day of college; we lived together sophomore year with six other girls where our TV was constantly abuzz with lowbrow television that was deeply meaningful to us, a true pop culture connoisseur—there is no one better to explain the pop culture phenomena that is Love Island than Bella.

Bella is from Bozeman, Montana and studies Health and Human Science at the University of Southern California. She loves to travel the world, touch grass, and listen to house music.

Here is Bella on Love Island, Season 7.

For those unfamiliar with the premise of Love Island: it’s a reality dating show where attractive young people live together in a beach villa, coupling up and competing for love. Contestants face a constant stream of challenges designed to test their relationships: new “bombshells” arrive to tempt committed couples, and other artfully manufactured scenarios guaranteed to create chaos. Throughout the season, the viewers vote for their favorite couples, and the winning pair receives a cash prize

I’m not an avid consumer of reality television, and the only time I’ve engaged with a dating show is to hate-watch Too Hot to Handle. But as I listened to a dinner conversation that was dominated by discussion of Love Island, I couldn’t deny my intrigue regarding the islanders and my desire to contribute to the psychoanalysis.1In the same way that last summer was deemed “brat summer2,” this summer had clearly become ruled by Love Island fanaticism.

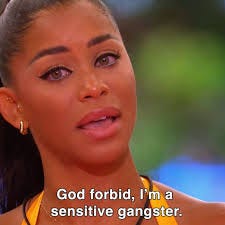

I started on Episode 14, which was the most recent at the time, and was quickly able to place a face to each name. “Hurricane Huda” was at her peak, and deeply embroiled in conflict with Jeremiah and the newest bombshell, Iris. “Amaya Papaya” was rising to stardom as a “sensitive gangster” full of “gratituilly,” and Ace and Chelley would soon enter a new couple.

The reality television I’d been socialized to hate was suddenly the highlight of my day. I love reality television. I love psychoanalysis. I love diving headfirst into cultural phenomena3 and finding meaning where others see drama. I love moments of self-reflection. I love sharing theories in group chats and sending TikToks filled with slow-motion edits and armchair commentary. I love to hate cancel culture—and I love the messy, necessary conversations it sparks.

Love Island became an object of analysis. A model for Gen Z dating,4 for influencer culture, for media consumption at its most participatory. I love how the public can’t possibly win. How the inherent narrative creation that occurs in reality television disrupts personal motivations. How we vote selfishly, but are always part of a larger collective—a system shaped and steered by producers, not unlike voters and politicians.5

“I love how the public can’t possibly win. How the inherent narrative creation that occurs in reality television disrupts personal motivations. How we vote selfishly, but are always part of a larger collective”

One moment that stood out was the portrayal of Huda and Chris’s relationship. As I remarked to a friend, “You have to be chronically online and obsessed with the show to have the best understanding of who to vote for.” The producers seemed to know that while devoted fans might read body language across episodes and follow social media to track support for Huda and Chris, casual viewers wouldn’t. So if producers wanted Amaya and Bryan to gain traction, they needed to present Huda and Chris as incompatible—carefully curating clips to sway the undecided.

Because Love Island—like love itself—is supposed to be about connection, not just brand deals or Instagram followers. The islanders who stay true to themselves, who don’t contort to fit a partner or a clique, are often the most secure. We could all take a lesson or two from Amaya.

One of the most exciting aspects of Love Island is watching the islanders after the show ends. No longer just objects of culture, they begin to actively participate in it.6 The narratives shaped by producers—and the audience’s opinions built on those edits—can now be challenged, complicated, or even overturned by how the islanders present themselves in the real world. They reclaim their voices, and we get to see who they are beyond the villa and the storyline they were assigned.

Love Island may not be high brow, but it’s the kind of media that allows you to think differently, feel more deeply, and form better connections with the people around you.7 It invites analysis, blends between entertainment and self-reflection, and helps me understand culture and myself a little bit better.

- Bella

Thank you for reading! I have compiled a lot of great reviews and insights and I am really excited to share them with you all. Like, share, comment, and subscribe to follow along—also so I can keep convincing people to take time out of their busy days to write for me.

Have great taste or know someone who does? Fill out this quick form.

The most fun part about watching reality television is watching it with other people.

charlixcx’s album brat last summer for those who live under a rock (don’t use social media)

Pop culture, no matter how “lowbrow” we deem it, is culture.

Unfortunately true.

Her genius mind.

Many of them have since been interviewed and profiled by mainstream news media.

Watching reality television with friends is one of the greatest joys in life